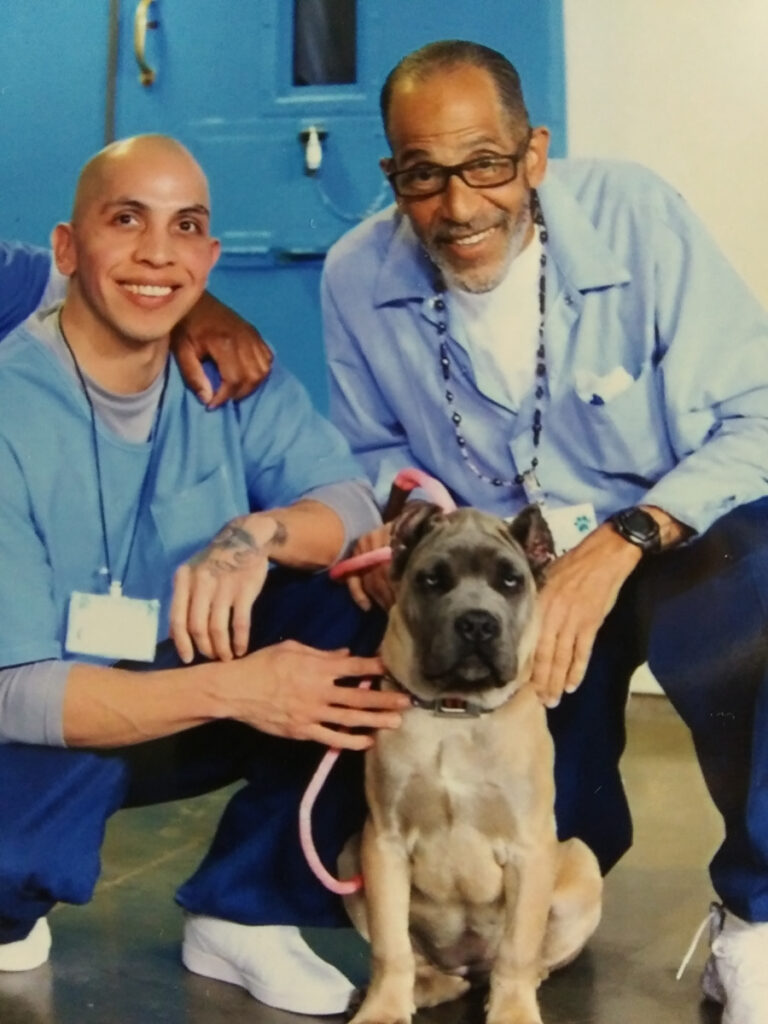

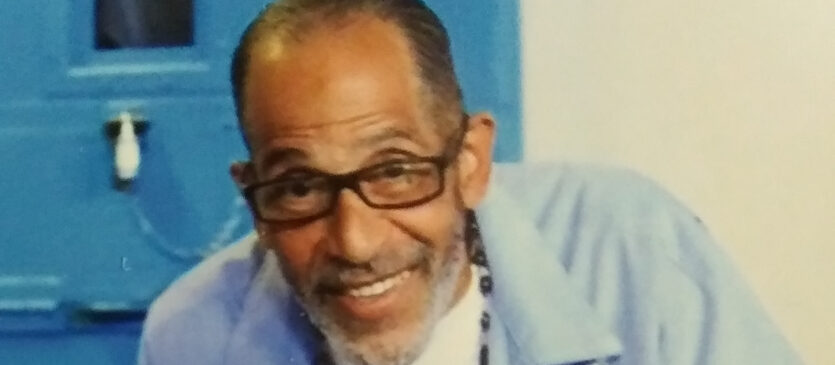

I’ve known Keith “Silk” Ross for nearly 40 years. From the moment I met him, while we were detained inside the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Men’s Central Jail, he was someone I held in high regard—not just because of who he was back then, but because of the man he’s remained despite everything the system has thrown at him.

Keith “Silk” Ross, a 72-year-old incarcerated man in California, is battling cancer while serving a life sentence for a crime where he wasn’t even the shooter. He has spent 33 and a half years in prison, even though Senate Bill 1437 (SB 1437), passed in 2018, was designed to prevent cases like his from resulting in such extreme sentences.

Yet, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and the parole board refuse to grant him relief. The speculation? Because the victim was a judge, making his release politically inconvenient.

This isn’t just about Silk. It’s about how the California prison system treats aging inmates, the failures of SB 1437 implementation, and why elderly prisoners with severe health issues remain incarcerated despite posing no public safety threat.

I sat down with Silk to talk about his case, his failing health, and the broken system keeping him behind bars.

I Wasn’t the Shooter

C-Note: Silk, let’s go back. A lot of people don’t know your case. Walk me through it.

Silk: This happened in 1991. A judge was shot in the leg, and three days later, he died. They said it was because the bullet hit his femoral artery. But I wasn’t the shooter. I never fired a shot. Even so, they convicted me under the felony murder rule and gave me Life Without the Possibility of Parole.

C-Note: And there was no robbery, no money taken?

Silk: Nothing but driver’s licenses. That’s it. But that didn’t matter to them. Once they decided I was guilty, the details didn’t matter.

The Law Says I Should Be Free—So Why Am I Still Here?

C-Note: Since we last talked, I’ve been looking at SB 1437. That law was meant for cases like yours—people convicted under the felony murder rule even though they weren’t the shooter, didn’t intend to kill, and weren’t acting recklessly. It was supposed to correct wrongful convictions by allowing felony murder resentencing.

Silk: I know. That law should’ve set me free. But the State ain’t trying to hear it.

C-Note: Why do you think they’re still holding on?

Silk: Because the victim was a judge. That’s it. The Board of Parole Hearings won’t touch this case because of who it was.

C-Note: So the law says you should be free, but politics says you gotta die in prison?

Silk: That’s exactly what I’m telling you.

They Are Letting Me Die

C-Note: Talk to me about your health.

Silk: I got cancer. They found a mass on my liver, and I’ve been going through radiation and chemo. The pain in my feet is so bad, I can barely sleep. But the worst part?

They don’t care.

I only see a doctor every two months. That’s it. And Telemed could be more frequent, but they just don’t make it happen. California Correctional Health Care Services acts like seeing a doctor is a privilege instead of a necessity.

C-Note: And when they take you to the hospital?

Silk: Man, that’s another punishment in itself. They throw me in a van, shackled like an animal, and haul me for hours to the Cancer Medical Center in Bakersfield. The whole time, I’m treated like I’m some young, dangerous dude trying to make a run for it. They keep a Mini-14 rifle and two sidearms on me the whole ride, like I’m about to pull off a movie escape. And not once do they give me anything to eat.

They Want You to Blame Your Parents

C-Note: The parole board—let’s talk about that. You spoke to a prison psychologist about your case, right?

Silk: Yeah. I thought we were gonna talk about who I am now, what I’ve learned, what I regret. But you know what she asked me?

She wanted me to blame my father.

C-Note: What?

Silk: Yeah. She wanted me to say my father was a bad parent. That my father failed me. That’s what they want—you to sit there and say, I’m here because of my parents.

But I wasn’t gonna do that. My father was a good man. When my mother died, he held our family together. He worked hard to make sure we were okay. I wasn’t gonna disrespect him just to satisfy some prison psychologist’s evaluation for the parole board.

C-Note: That’s part of their game, though. They want you to say your parents were bad, that you came from some broken home, because that makes it easier for them to check a box.

Silk: Right. And if you don’t say it, they act like you’re not taking accountability. Like you’re not ready for parole.

C-Note: But what if the real problem was poverty? What if it was the system? What if it was the lack of opportunities for Black men?

Silk: Exactly. But they don’t wanna hear that. They don’t wanna admit that the California parole board has a racial bias or that Black men are denied parole at higher rates.

What Threat Do I Pose?

C-Note: Let’s be real. You’re 72 years old. You’ve done 33 and a half years. You’re dying in here. Why do you think they won’t let you go?

Silk: Because they can. That’s it. But tell me—what danger do I pose to anybody?

C-Note: None.

Silk: Right. I see people getting compassionate release all the time. People with worse cases than mine. People younger than me.

But they look at me and say no.

C-Note: And you think it’s because the victim was a judge?

Silk: No doubt about it. This ain’t about justice. It’s about power. It’s about the system refusing to admit it made a mistake. California has a compassionate release process, but it only seems to work for some people. They know I’m too old and too sick to be a danger to anyone. But instead of granting me release, they’d rather let me die in here just to protect their own image.

C-Note: So even though the system claims to have programs for geriatric prisoners, for sick prisoners, for compassionate release, they still won’t let you out?

Silk: That’s exactly it. They’d rather spend money keeping me locked up than admit they were wrong.

Set Silk Free

Keith “Silk” Ross deserves to go home. He deserves to spend his final days with dignity, surrounded by the people who love him—not locked in a prison cell where his suffering is ignored.

SB 1437 was passed to correct sentencing injustices like his, yet California refuses to apply it fairly. His age and illness alone should make him eligible for compassionate release, yet the system holds on.

This isn’t just about Silk. It’s about a prison system that punishes long after justice has been served. The refusal to release elderly, terminally ill inmates isn’t about public safety—it’s about political self-preservation. If something doesn’t change, the State of California will let Silk die in prison—not because justice demands it, but because bureaucracy allows it.

The Cost of Keeping Elderly Prisoners Behind Bars

P.E.A.C.E. fights for elderly prisoners with health issues—not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because the cost of keeping them incarcerated is a growing crisis. The financial burden of armed housing, high-risk medical transport, and specialized prison healthcare for elderly, dying inmates is staggering—one that drains resources without benefiting public safety.

California taxpayers are paying for round-the-clock security and expensive prison healthcare for men like Keith “Silk” Ross, a 72-year-old battling cancer who poses no threat to society. The money spent shackling men like Silk to a hospital bed could be redirected to education, healthcare, and community programs—investments that build rather than break lives.

This isn’t just about wasted tax dollars—it’s about values. How much longer will California continue spending millions to incarcerate the dying when compassionate release offers a solution that is both just and fiscally responsible?

The system won’t give Silk justice.

But we can make sure he is heard.

Set Silk free.

Leave a Reply